Losing Team

Z and I sit across from each other at Klein’s Bakery. He is shopping for a new phone case even though his phone is shattered so severely that his phone’s innards are visible from the reverse side. You should read this short essay, I say and hand him the leftist magazine I subscribe to, and I will see if I can find you another phone case, maybe one with Caroline Polachek or Phoebe Bridgers on it. The essay is about Jay’s Treaty, a 1974 agreement between Great Britain and the United States that included provisions allowing Native Americans to travel freely between the US-Canada Border. The author Julian Brave Noisecat writes about the treaty to explain why he can cross the border without a passport, uses it to describe borders as an arbitrary imperial invention, and questions why Guatemalan immigrants in their Washington state town, many of whom speak Mayan languages and wear traditional textiles, don’t have the same right to live and work in the US as Indigenous peoples.

What do you think? Z asks after closing the magazine. I am stumped, bamboozled by the impressive, multigenerational reach of this legislation and frustrated by the oppressive political machine we live inside that continually determines whose lives matter and whose don’t, but I cannot sum up this sentiment and make a dumb observation instead: It is crazy how the federal government shapes our lives. Z pauses thoughtfully and prompts me further. How does the federal government impact your everyday life? I feel the urge to say, That’s a really good question, with the generous tone of a panelist who is trying to establish good will with a moderator so that they are invited to future conversations even if their question was unremarkable. But I feel myself become entangled in the question, experiencing a sudden sense of dread, the same that I encounter whenever I sit in front of an empty sheet of paper knowing I must decide what I find important enough to write about. Ah, it is a good question.

I begin: the price of gas, groceries, or my estradiol prescription. My general sense of safety, I guess. Hmm. My guilt, or shame, or outrage, knowing that my taxes fund bombs and violence; today, the assassination of Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran and Fuad Shukr in Beirut, both accelerating wider conflict in the Middle East; 15 murdered during an Israeli strike on a school sheltering displaced Palestinians; and at least 15 killed following election results in Venezuela, whose economy is paralyzed by US sanctions.

In May, Z bought tickets for the two of us to watch the Cubs play the Atlanta Braves at Wrigley Field. We ordered two hot dogs and beer. One of the concession workers offered us a discount if we paid in cash, so I surreptitiously passed her a twenty-dollar bill that I earned selling books at Myopic a few days earlier, which she pocketed, both of us delighted to cheat the concession company of its profit and avoid paying tax on the exchange. After the Braves’ pitcher struck out half a dozen players, the crowd became restless and began filtering out of the stadium. Bored, I googled the capacity of the stadium—40,000. That’s almost the same number of Palestinians killed in Gaza, I remarked and looked around the stadium, trying to conceptualize death at such an immense scale. Z thought such enumeration was an ineffective, misleading comparison because it obscured the destructive violence of Israel’s months-long genocidal campaign, giving the impression it would be easy to gather and quickly kill such a large number of people by gathering them into roughly the space of a city block. I agree, in principle, because the sum itself can never represent the grim reality, five numerical digits intended to account for thousands of individual lives. But I cannot decide if it matters how I personally describe or account for the scale and inhumanity of state violence if such description does not slow the perpetrators or aid the victims. Z and I stayed until the end of the game even though it was clear the Cubs had lost.

I continue my list. Maybe infrastructure, the nonstop construction on Milwaukee Avenue that started in earnest this spring when Capitol Cement tore up the south sidewalk from Central Park Kimball, improvements made possible by Joe Biden’s 2021 Infrastructure Bill, a piece of trivia I learn from a massive sign the city erected on the lawn of Comfort Station, a sign I first noticed the night Thomas Matthew Crooks attempted to assassinate Trump but missed, the bullet clipping his ear. Z and I sat on the grass beneath the Logan Square Monument, ate an overpriced Sweetgreen salad, and showed each other funny tweets about the assassination attempt. My favorite, the photo of Trump raising his fist in defiance, blood dripping from his ear, with the caption, Do NOT get your ears pierced at Claire’s. Both of us glumly recalled the fervor that overtook Chicago when Biden defeated Trump four years prior, silently imagining the celebrations we might be indulging in if the bullet had not missed. We could’ve gone to a bar and done a shot, I suggested.

The sign is very important to Brandon Johnson, Kitty tells me on Sunday evening as Inés’ performance starts, four performers circumambulating the blue metal structure on Comfort Station’s lawn. Oh, I’m sure, I say. Kitty says they hid the sign underneath the bushes before the Txa Txa dinner because it was “killing the vibe.” Kitty is less interested in talking about the sign, or Joe Biden, or Brandon Johnson. Instead, Kitty lays down in the grass beside me and explains that they received a phone call from their neighbor the night prior. The phone call was not from their neighbor though. It was from the Chicago police. They evacuated Kitty’s apartment and borrowed the neighbor’s phone after Comfort Station received an email that threatened to bomb Kitty’s apartment, Kitty’s coworker’s house, and Comfort Station because they were hosting a drag performance on the lawn. The Bomb Squad arrived, twenty officers and one canine, and searched the lawn. I look around. There are no visible scorch marks or debris; there was no bomb. Because the conclusion of Kitty’s story is evident, I express sympathy. It must be so unsettling to have someone threaten your home. I wonder how they found your address?

Kitty is surprisingly jovial, nodding their head seriously and laughing as they describe rushing home to speak with the police. Kitty’s laugh is effusive and pressurized, like a steam kettle’s whistle. I shift my gaze from Kitty’s face to the performers, one of whom grips the side of the blue structure and shakes the metal panel ruthlessly. I am supposed to be taking notes so that I can write about the performance later, but my focus drifts back to Kitty, who continues their story. I wonder if their lighthearted retelling of the story is an attempt to defang the threat by transforming it into a comedic bit, albeit one without an explosive conclusion. Their expression goes blank for a moment as they describe a similar bomb threat against Women & Children First bookstore’s drag reading, and we both nod our heads silently, considering the transphobia and homophobia motivating these senseless threats, and the possibility that they could escalate to actual violence next time. I consider, too, that Kitty might be amused by the bomb threat because the story creates affinity, like a community coming together after a disaster destroys homes and businesses and upends daily life; A mutual friend once confessed to me that whenever they had an idea for a event or project beyond their skills to realize they talked about the idea around Kitty, who is famed for their production and organization capabilities, until they offered to help. Their animation, I imagine, inspired by their newfound responsibility, this exalted role, as a buffer between the performers, the police, and the specter of the explosive device

A crowd of police remained on the lawn of Comfort Station while the drag performers continued their set in defiance, but Kitty ushered them away, unnerved by their presence. One officer remained in his car to observe. Kitty abruptly finishes their story, sheepishly realizing they’ve dominated the conversation, and asks me how I am doing. I wave my hands ambivalently, like a dog fidgeting at the edge of a bed, trying to decide if it can make the jump. I land on a simple, punctuated statement. It’s been a busy summer. We are both silent afterward and watch Inés’ performance, which is funded, in part, by the National Endowment for the Arts, a fact I dutifully note so that I might mention it to Z later.

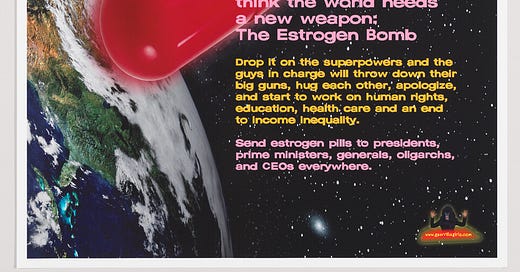

Image: Guerrilla Girls, The World Needs a New Weapon: The Estrogen Bomb, 2012.